Female activism is on the rise in the Muslim world, pandemic notwithstanding

Muslim Women’s Day fell on 27 March this year, giving female Muslims the opportunity to have their voices amplified in the mainstream media. Its importance should not be undervalued, as Muslim women both in the East, and in the West have historically been marginalised. But, far from silent and submissive (stereotypes too often attributed to us), women are rising up and demanding change in the Muslim world – and make no mistake, their voices are being heard.

We’re now witnessing very welcome legal reforms that have adapted to the evolving lifestyles of women in the Middle East. In 2019, Saudi Arabia began passing laws that were fundamental to women’s rights – including the right to drive and new protections against sexual harassment. As part of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030, more opportunities are opening for females, who are being encouraged to enter the workforce; as of February 2021, they have the opportunity to take up arms and enter the military. At the end of 2020, widely celebrated legal reforms in the UAE also made significant headway for women’s rights – particularly in abolishing the cultural ‘honour-killing defence’ which previously gave men who murder their female family members in order to ‘defend their honour’, more lenient punishments. A socially ingrained gender divide puts females at higher risk of abuse and violence, from which women suffer frequently across the globe, but without a legal framework in place to protect victims, they are close to helpless in attaining any justice. “A lot of the social, legal and political practices in the Muslim world are built upon this system of hierarchical obedience that’s very patriarchal and that places the older man at the top of that pyramid,” explains Kuwaiti women’s rights activist, scholar and lecturer, Alanoud Alsharekh, who co-founded Abolish 153, an initiative aiming to put a stop to domestic violence in Kuwait. It campaigns to repeal Article 153 of Kuwait’s penal code, which prescribes a minimal punishment for perpetrators of honour killings. Alsharekh explains that Article 153 is neither sacred nor religious – it comes from the Napoleonic Code, much of which was drawn from ancient Roman law. Segments of these Western codes were often copied by Ottoman penal codes and later helped shape the independent legislature of many Arab nations.

Motivated by the pressing need to dismantle social and legal norms that are rooted in patriarchy and detrimental to women, many activists are revisiting sacred scriptures to help promote reform from a faith-based perspective. A new group of Muslim feminists has emerged, who believe that upholding justice and fighting against oppression is fundamental to the essence of the faith. “Islam actually gave women rights long before many other cultures and religions did,” points out Dubai-based modest fashion designer Safiya Abdallah, referencing the revolutionary legal reforms in areas of marriage, inheritance and property that the faith brought with its revelation. Muslim feminists point out that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was a role model in how he treated his wives, and encouraged female participation in society in early Islamic history. “The first Muslim was a woman, the first martyr was a woman, and Islam descended upon the Prophet (PBUH) in a house full of women,” says Alsharkeh. “Islam is an activist religion, and I see it as a feminist religion,” she continues. “My faith informs not just my activism but everything that I do.” Witnessing stark discrepancies in gender rights in the Arab world led Alsharekh to pursue a career in women’s rights reform. As a student, she left Kuwait for the UK during the Iraqi invasion, and returning to the country years later found her calling as an activist, helping campaign for a 1999 bill that would grant Kuwaiti women the right to vote. “We lost that bill, and [feminism] stopped being something abstract and became something really personal and real,” she says.

Alsharekh is just one of many female activists working to improving the position of women in the MENA region and beyond. Numerous organisations dedicated to women’s rights have emerged across the region – from Jordanian feminist collective Takatoat, which establishes safe spaces for women to protect them from gender-based violence, to Lebanon’s Fe-Male that aims to fight sexist representations and advertisements of women in the media. And while legal reform is key in protecting women’s rights, instilling awareness within the community is equally critical in ‘unlearning’ cultural customs that might be sexist. Along with providing care and rehabilitation services for female victims of abuse, the Dubai Foundation for Women and Children (DFWAC), for instance, hosts training sessions and educative programmes to help raise awareness among the public. This year, DFWAC teamed up with YSL Beauty for the brand’s international ‘Abuse is Not Love’ initiative to help combat intimate partner violence, which one in three women reportedly experience.

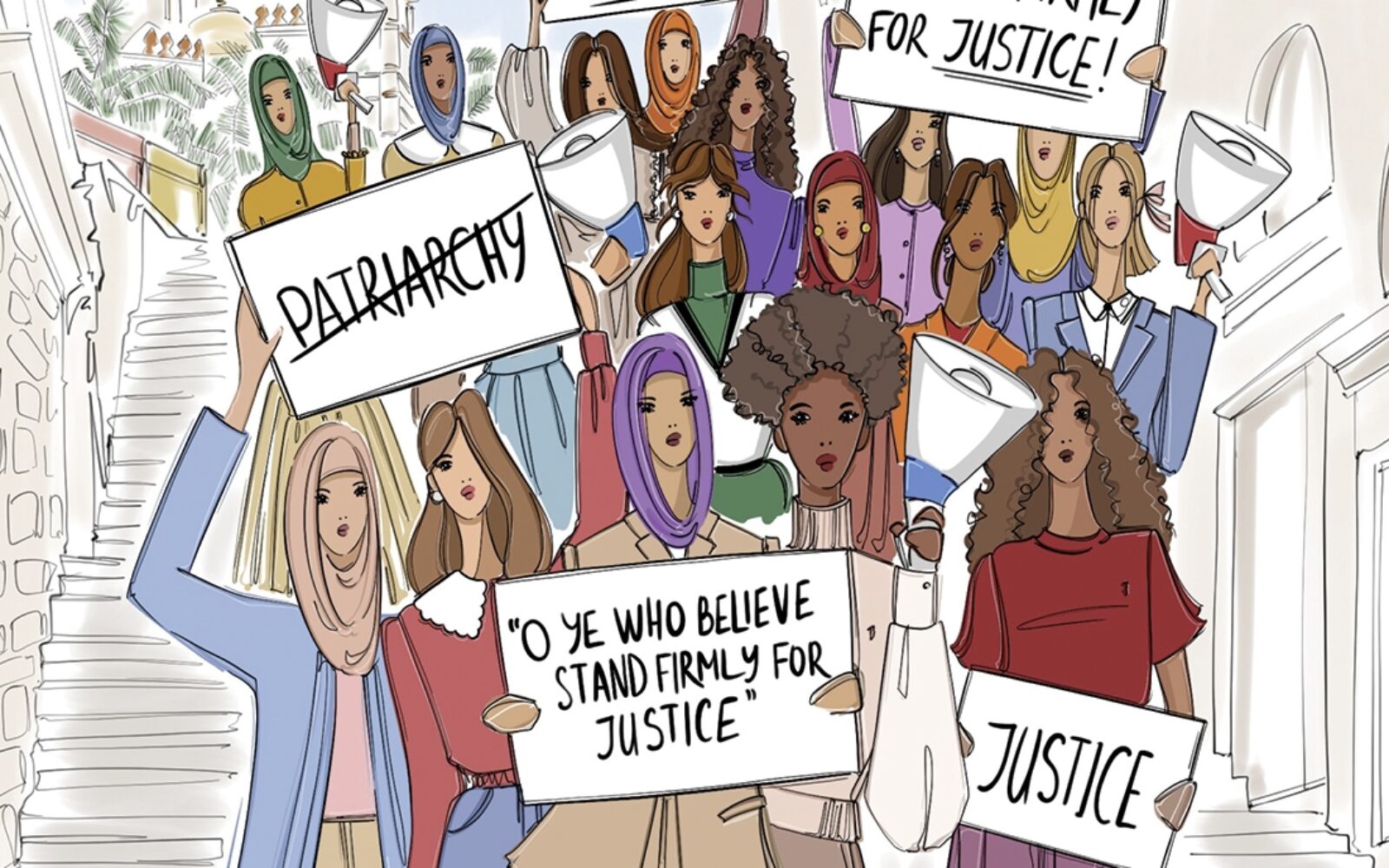

Artwork by Daria Stephenson

Some NGOs and activists imbue their missions with religious motivations and language – Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality (WISE) works to empower women and achieve gender equality while acknowledging the rich history of Islamic jurisprudence and legal traditions. Alsharekh explains that a reformist approach from a religious, rather than secular, framework of morality is the natural one to take: “It is easy to frame it this way because it is this way,” she says of Islam’s egalitarian spirit. “Today, knowledge and access to knowledge is being democratised – people are coming back to the purity of Islam.” Lifting the veil between religion, culture and politics is no simple feat, but there are female Muslim trailblazers stepping up to the task, the most notable among them being, of course, Malala Yousafzai, who appeared virtually at this year’s Emirates Airlines Festival of Literature. Yousafzai epitomises the relentless perseverance of female activism – her experience of being shot as a teenager by an extremist faction of the Taliban deterred her from neither her faith nor her plight to make education for girls accessible in Pakistan. Now she stands as a beacon of progressive activism in the Muslim world and beyond.

“With the devastating aftermath of colonisation and its intellectual branch of Orientalism, reducing Islam and Muslims to mere caricatures, it is important that the Muslim subject position be allowed to reclaim Islam and to reform it once more, guided by the eternal principles of Islam and the pressing needs of the community today,” explains Dr. Sofia Rehman, a UK-based academic who leads virtual book clubs centred on readings of gender and faith. Those pressing needs are almost always motivated by a desire to seek justice, which is enjoined on Muslims time and again in the Quran and Hadith (sayings) of the Prophet (PBUH). The pandemic, believes Rehman, has further called into question the treatment of minorities and the disparities between genders in communities across the globe, making the call for continued change ever more critical. “The pandemic has stripped the world of its pretences. We have seen the eruption of the Black Lives Matter movement, we saw the statistics that the coronavirus has claimed more lives from among the poor and the marginalised not because their DNA made them more vulnerable to the virus but because power structures and the way society is organised did. We have seen that women have been worse affected economically as the responsibility of children at home has squarely rested on them,” she explains. “This pandemic has laid bare the inequities in the world we inhabit, and there are people who will not abide them.”

Social upheavals are rarely achieved overnight, but feminist and activist groups in the Middle East are nonetheless making headway with building community awareness and campaigning for positive change. Women are also being increasingly appointed as high-level leaders with significant influence and decision-making capabilities – in March 2021, the UAE Securities and Commodities Authority announced that listed companies in the nation need to have at least one female director on their boards. Though the term may still carry taboo connotations in some communities, feminism, says Abdallah, is simply about treating and judging men and women equally based on their work and merit. “The way I look at it, it’s about hearing us in the same way a man would be heard, and viewing us and respecting us in equal ways as well.”

Women are the Future of Islam is the title of the book by Sherin Khankan, the founder of Copenhagen’s Mariam Mosque for females, epitomising the optimist outlook, vocal vehemence and fierce fervour driving the determination for reform. For while there is still plenty of work to be done in the realm of women’s rights, the door has been thrown open to having conversations that help bridge the gender divide in the Muslim world.

Read Next: Hafsa Lodi on What’s Fuelling the Modest Fashion Movement

- Words by Hafsa Lodi

- Artwork by Daria Stephenson