Peggy Guggenheim certainly lived up to a name that is synonymous with the art world. Deeply involved in the rise of modern art, her personal life frequently, and controversially, intertwined with those of the artists themselves. A documentary film directed by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, Art Addict, explores the life of this avid collector.

Kandinsky or Dalí, de Kooning or Pollock, take your pick from some of the most influential modern artists of our time. The breadth of the collection that nestles on the banks of the Grand Canal at Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Venice, now the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, is breathtaking even to the untrained eye. Art Addict, directed by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, delves into the world of the woman who amassed the collection over the course of her life, devoted to sharing it with the world. The film, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and features on the program at Art Basel, is based on the lost 1978 recordings of interviews between Peggy and Jacqueline Bograd Weld, author of the only authorised biography of Peggy, Peggy: The Wayward Guggenheim. Vreeland re-discovered the tapes in a shoebox in Jacqueline’s basement. ‘There’s nothing more powerful than when you have someone’s real voice telling the story,’ Vreeland recounts at Tribeca. ‘You can tell it was hard for Peggy… because she wasn’t someone who was especially expressive; she didn’t have a lot of emotion.’

Peggy was born in New York in 1898 into the Guggenheim fortune. A fortune acquired by Peggy’s Swiss grandfather, Meyer, who arrived in the US in 1847 and succeeded in the mining industry. Peggy’s uncle, Solomon, a prolific modern art collector, would go on to found the Guggenheim Museum. Yet her family name proved to be an advantage that did not guarantee a carefree upbringing. Her father, Benjamin Guggenheim, perished on the Titanic in 1912 – wearing full evening dress, he and his assistant helped women and children off the ship, resigned to their fate and prepared to do their duty ‘like gentlemen’. The family had already lost some of their wealth through Benjamin’s business ventures and the young Peggy felt stifled by her regulated life in New York, fitting neither into her family nor her times. ‘My childhood was excessively unhappy,’ she once wrote. She sought out an alternative way of living, moving to Paris in 1921 and marrying Laurence Vail, a writer and Dadaist who was part of the Parisian bohème that so enthralled her. Identifying with these outlandish and freethinking artists gave Peggy a new lease on life in a way that was completely unconventional for women of her time.

Peggy Guggenheim (standing) in Paris in the 1920s with British artist, Mina Loy. Image courtesy of Corbis

Vreeland tells a weaving story of a strange and complicated woman, dealing with a certain pain in her own way. Interviews with artists and art experts fill in the blanks. John Richardson, a biographer of Picasso’s, plays a prominent role in telling Peggy’s story, and art world figures, such as Marina Abramovic and Larry Gagosian, speak of how her collection has influenced the current scene. Vreeland has form for selecting subjects who are not accustomed to conforming. In 2011 she directed critically acclaimed Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel. As Diana Vreeland’s granddaughter-in-law, Lisa had a close connection to the story of the fashion visionary. Is Peggy her art world equivalent?

She was smart enough to ask Marcel Duchamp to be her advisor – so she was in tune, and very well connected.

Lisa Immordino Vreeland

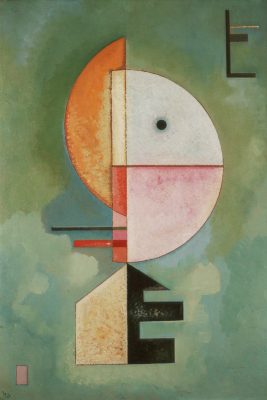

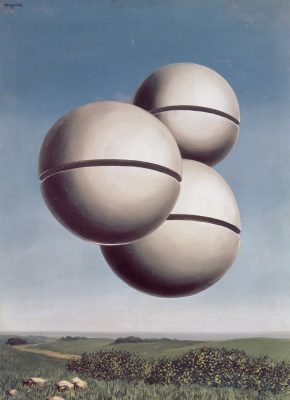

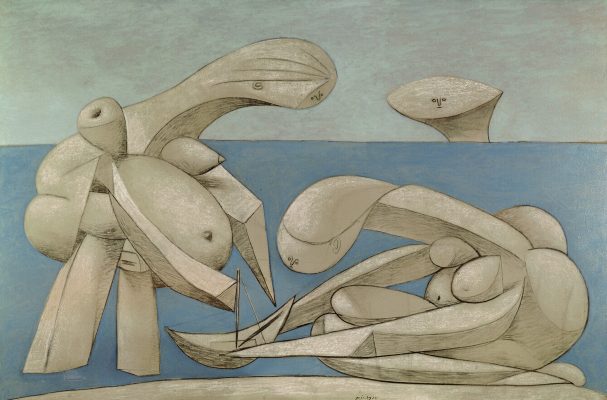

‘Peggy was also a visionary but emotionally she was not as alive… This film is rich with the lives of the most important artists of the time – and Peggy is the centre of the action,’ says Vreeland. Peggy made it her business to be at the centre of the action. Opening her first gallery in London in 1938, the Guggenheim Jeune Gallery, showing works by Jean Cocteau and later Vasily Kandinsky, she was encouraged to dedicate her life to contemporary art (‘a living thing’) by Samuel Beckett. She continued to collect works throughout the Second World War for the modern museum she had planned. ‘She was smart enough to ask Marcel Duchamp to be her advisor – so she was in tune, and very well connected,’ says Vreeland. Peggy resolved to ‘buy a picture a day’ and acquired masterpieces by Piet Mondrian and Salvador Dalí, only fleeing soon-to-be-occupied France with her treasures after she had completed her purchase of Brancusi’s Bird in Space. She later championed Jackson Pollock through the key moments of his career, supporting him with monthly allowances and commissioning his largest painting, Mural. Without her patronage, the American abstract expressionist movement might not have thrived.

Yet the sadness in Peggy’s life is an unavoidable theme in the film. She left Vail, who used to beat her, for English intellectual and war hero John Holms in 1928, giving Vail custody of her son Sinbad (but not daughter Pegeen). Peggy married uber-surrealist Max Ernst in 1941 (whom she loved ‘because he was so beautiful and because he was so famous’) but they separated two years later, divorcing in 1946. She documented her own tumultuous personal life in a scandalous autobiography, Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict. Peggy was unabashed about revealing her many adventurous liaisons with the likes of Marcel Duchamp and artist Yves Tanguy, which have since threatened to overshadow her artistic legacy. A default way of connecting with the important men in her life perhaps, driven by her complex childhood. ‘I think it was really [bold] of her to have been so open about her sexuality, this was not something people did back then,’ says Vreeland. And yet Vreeland notes that despite the men that surrounded her, Peggy’s sense of loneliness and loss never really left her – instead the void was filled, or displaced, by her beloved art. A guiding force in recognising modern art’s greatest talents, Peggy died in 1979 at the age of 81, clinging to every second of a life of reinvention. ‘It’s horrible to get old. It’s one of the worst things that can happen to you,’ she said, ‘But I really felt I accomplished what I wanted to do, and I’ve done it very successfully, and I’m very happy about that.’ Thanks to Vreeland’s insight immortalised on film – ‘It was her ability to redefine herself in the end that truly summed her up’ – and the lasting legacy of the rare collection of the most visited modern art in Italy, Peggy Guggenheim’s artistic legacy lives on.