When Claire Choisne, Boucheron’s creative director, met the Maharaja of Jodhpur, His Highness Gaj Singh II, three years ago and began working with him on ideas for a new High Jewellery collection, she was following a well-trodden path.

Boucheron already had deep historic links with India – and it was not alone: Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Chaumet and Mellerio were among other houses that had fallen under India’s spell in the late 19th to early 20th century, particularly the spell of its Mughal past and the wonderful art and jewellery designs produced during this Golden Age. The love affair between the jewellers of Paris and the subcontinent goes back even further, to gem-trader Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who travelled to Persia and India between 1630 and 1668, when the wealth and culture of the Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan, fully matched that of France’s Louis XIV. Established in 1526 when Babur, a conqueror from Central Asia, overthrew the Lodi dynasty in northern India, the Mughal Empire gave birth to a sophisticated and progressive civilisation. Art and architecture flourished, blending Islamic, Hindu and Persian traditions, creating one of history’s greatest legacies of artistic craft, jewellery and precious ornaments. Mughal style has had an immeasurable impact on Western aesthetics and it remains a source of inspiration today – Claire Choisne’s trips to India was just one manifestation of this.

When Claire Choisne, Boucheron’s creative director, met the Maharaja of Jodhpur, His Highness Gaj Singh II, three years ago and began working with him on ideas for a new High Jewellery collection, she was following a well-trodden path. Boucheron already had deep historic links with India – and it was not alone: Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Chaumet and Mellerio were among other houses that had fallen under India’s spell in the late 19th to early 20th century, particularly the spell of its Mughal past and the wonderful art and jewellery designs produced during this Golden Age. The love affair between the jewellers of Paris and the subcontinent goes back even further, to gem-trader Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who travelled to Persia and India between 1630 and 1668, when the wealth and culture of the Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan, fully matched that of France’s Louis XIV. Established in 1526 when Babur, a conqueror from Central Asia, overthrew the Lodi dynasty in northern India, the Mughal Empire gave birth to a sophisticated and progressive civilisation. Art and architecture flourished, blending Islamic, Hindu and Persian traditions, creating one of history’s greatest legacies of artistic craft, jewellery and precious ornaments. Mughal style has had an immeasurable impact on Western aesthetics and it remains a source of inspiration today – Claire Choisne’s trips to India was just one manifestation of this.

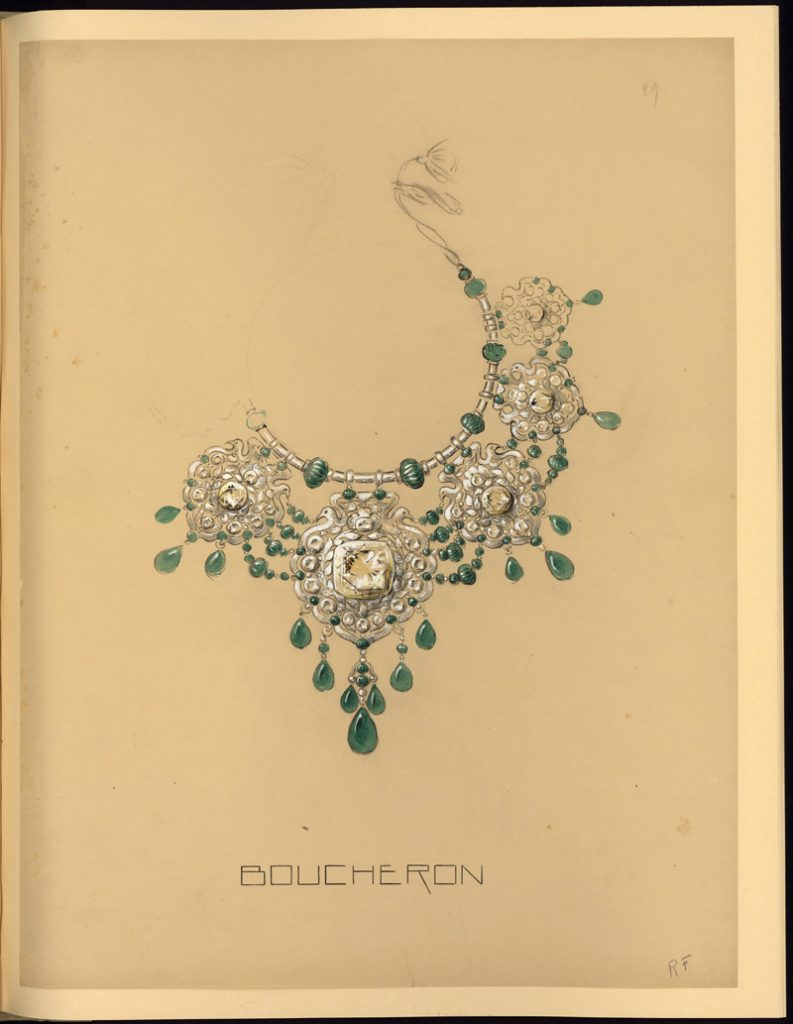

As the Mughal Empire declined, the Maharajas, the provincial rulers to whom Delhi had long delegated a lot of power, retained their wealth – and their penchant for fabulous gems. Towards the end of the 19th century, Britain’s growing power in India had a huge impact on English style and, in 1901, the soon-to-be Queen Alexandra (wife of King Edward VII) asked Pierre Cartier to create an Indian-style necklace using rubies, pearls and diamonds that were already in the royal collection. At the same time, India’s princes had begun patronising European jewellers: The Maharaja of Kapurthala and Maharaja of Lahore were clients of Boucheron by the mid-1890s. In 1903, Louis Boucheron took over running his family’s business and, in 1909, made his first trip to India to buy stones, especially Kashmiri sapphires – among them a cabochon sapphire. Not previously seen in Western jewellery, the cabochon sapphire helped trigger a new style and became an emblem of the house. Also, in 1909, Jacques Cartier took over the London branch of the family firm from his brother Pierre, and was given responsibility for all of its Indian business. Making his first trip to India in 1911 to visit potential clients, he was hugely impressed by Indian regalia, the vivid colours of the stones and cloisonné enamel used in their design, and the Indian style of polishing rather than cutting. He began buying emeralds, rubies and sapphires. As the 1920s dawned, the use of coloured stones and Indian influences by these two maisons, among others, became one of the first great stylistic innovations of the Art Deco period. Polished and carved stones, tassels, animal-head bangles, paisley shapes – all were an exciting change from the staid and fussy ‘garland’ style that had dominated European style for decades. In 1924, Cartier created a sautoir using pale blue Kashmiri sapphires and carved emeralds, which Baron Eugène de Rothschild bought for his new bride (it was sold at Sotheby’s New York in April 2015).

[pullquotes bg_image_id="32751" quote=""Now, as I look at the Rewa jewels and the Golconda diamonds and the Oriental pearls that I brought back from other places, I can feel all the exotic poetry symbolised by the magnificence of the ‘Thousand and One Nights’ legend and the romance of the Taj Mahal,” - Claude Arpels" quotee=""]

At the Paris exhibition of 1925, Cartier revealed its first bracelet to use the Mughal-inspired mixture of carved and cabochon emeralds, rubies and sapphires – a style that became one of the most celebrated jewellery designs of all time and was nicknamed ‘tutti-frutti’. An example made by Cartier New York around 1928 was sold last year by Evelyn Lauder in a charity auction for a record $2.1m, demonstrating the exceptional collectability of these pieces.

“With the mixed colours, stones and cuts, and the lightness of the platinum settings, this jewellery really was for Western, not Indian clients,” says Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s Image and Heritage Director. “But, it took a certain kind of woman to wear them – a woman who was not just elegant, but had great taste and audacity.” Among these women was Doris Duke, the heiress to a huge tobacco fortune. On a honeymoon tour of Asia with her husband James Cromwell, she fell in love with the Oriental style and, besides building a large collection of Indian and Southeast Asian jewellery, she chose pieces by Cartier and David Webb that incorporated Eastern gems and motifs. However, her taste for exotic style had developed even before that first trip to India: In 1934 she had bought one of Cartier’s Mughal-inspired bracelets in emeralds, pearls and diamonds, and a matching clip. Probably the most famous of all the ‘tutti-frutti’ pieces is the Collier Hindou necklace, commissioned from Cartier Paris in 1936 by Daisy (Mrs Reginald) Fellowes, heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune. A spectacular concoction of sapphires, emeralds and rubies – in a mix of cabochons, beads, briolettes and carved stones, mostly from pieces already owned by the client – as well as diamonds, platinum and white gold, it was bought back by Cartier at auction in 1991 for its Historic Collection.

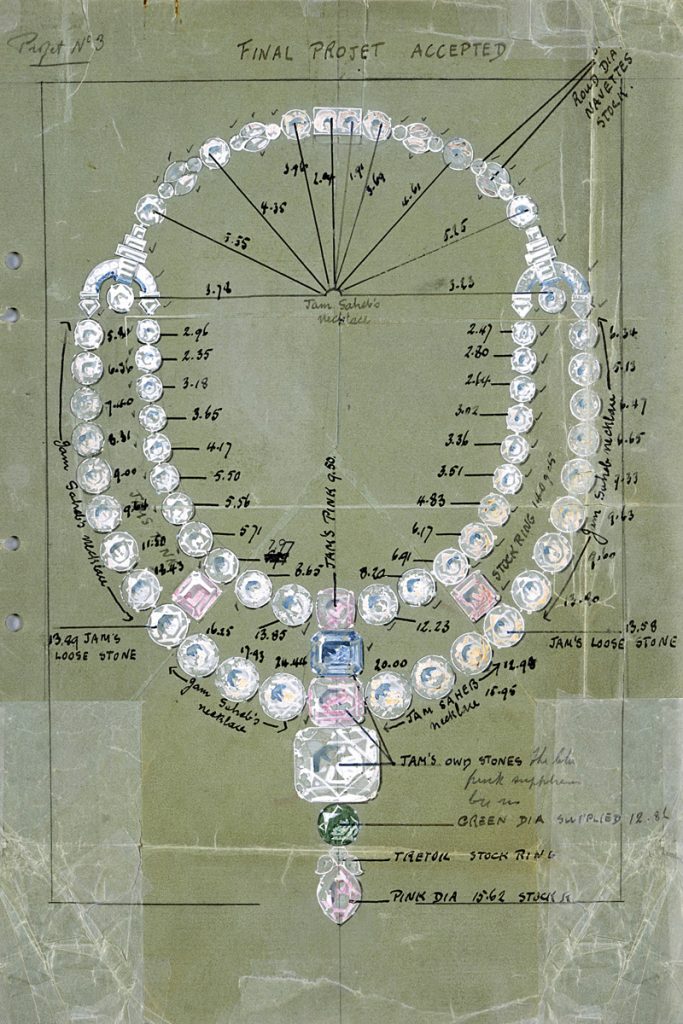

Meanwhile, as the great French firms looked towards Mughal India for design inspiration, the great families of India were turning to French and English houses to rework their Mughal pieces in the European way; indeed, some of the biggest customers that Cartier, Chaumet, Van Cleef & Arpels, Mellerio, Mauboussin and Harry Winston enjoyed were Indian royal families. Among them was the Maharaja of Patiala, who – as well as commissioning Boucheron to transform his staggering collection of emeralds and other stones into 150 pieces of Indian-style jewellery – was an enthusiastic patron of Cartier and other Place Vendôme houses. The key point of this Mughal-European mix is that the influences worked both ways. It was not a slavish copying of either style; rather, the essence of each was extracted – on the one hand, the flamboyant spirit and colour of Indian jewellery was translated, via European techniques and style, into something much more airy and light; on the other, refined European settings and cosmopolitan tastes added sophistication and modernity to the more overtly ‘Indian’ pieces.

At the end of the 1940s, following Indian independence and the Partition, several of the Maharajas and their wives exiled themselves to Europe, taking some of their finest jewellery with them. None was more colourful than Sita Devi, the Maharani of Baroda, a great beauty whose love of jewels was matched only by her love of parties (and consummate skill as a hostess). Choosing Van Cleef & Arpels as her jeweller, she commissioned about 100 major pieces between 1949 and 1967, as well as buying countless ‘everyday’ pieces from stock. Among the most notable commissions was a wonderful necklace of pear-shaped emerald drops suspended from diamond-set ‘leaves’ – the Mughal influence subtly present in the paisley-shape of the leaves and, of course, the emeralds themselves. A 1954 necklace of cabochon rubies and emeralds with diamonds was unquestionably modern and European, yet the mixed colours and cabochon cuts whispered ‘Mughal’. These dynastic influences continued to appear throughout the 1950s in various guises – for example, in Cartier’s Tiger bracelets, worn by the Duchess of Windsor, and in a variety of peacock-motif jewels from different houses – before becoming a full-blown craze again in the 1960s and ’70s.

1. Cartier's new interpretation of 'tutti-frutti' | 2. Amrapali, earrings in white gold and diamonds | 3. Cartier's Etourdissant collection showcased the Hyderabad headband | 4. Chopard earrings in white gold, diamonds and cabochon emeralds^

Riding the wave of Cinecittà and la dolce vita, Bulgari became one of the most sought-after names of those decades. Its instinct for colour, bold handling of gold and use of cabochon stones – often seen all together in show-stopping bib-style necklaces – put a new, original and utterly modern spin on Mughal style. David Webb, the quintessential American jeweller of the 1960s, often used imagery based on his studies of 18th-century jewels from Jaipur, India. For Doris Duke, he made a spectacular ruby and pearl necklace that tempers New York sophistication with a Mughal spirit. At Van Cleef & Arpels, there was a great surge in commissions for Mughal-inspired designs as new clients joined the Maharani of Baroda (perhaps even influenced by her status as a high-society tastemaker). Another influence was Claude Arpels’ marriage in 1970 to Pakistan-born Mherulisa, known as Malou and a woman of great taste, whom he had met when he was in India on one of his many stone-hunting trips – he called them ‘jewel safaris’. The commission to design the coronation jewels for the Empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi, exposed the Maison to the motifs of Persia – a crucible of Mughal style. Among the work produced by the Maison during this period, one of the finest examples is the magnificent necklace of carved emeralds, diamonds and yellow gold in 1970 for the Begum Aga Khan.

“Many clients continued to bring their own stones, and often, the designs would be much more opulent than the usual house style,” says Catherine Cariou, Heritage Director at Van Cleef & Arpels. “It was a wonderful, extravagant period and I think that if the same clients came to us today, we might not accept some of the commissions as they would be so far outside the house style.” Today, Mughal style continues to inspire and influence designers in countless ways. In 2004, Jeremy Morris, then creative director of David Morris and now its CEO, designed an eternity ring for his wife, Erin, using rose- cut diamonds. Why the 18th century cut? “The beauty is in its many facets, giving it a delicate, romantic and almost translucent feel,” he explains. The rose cut has not only become a house signature of David Morris, it has been adopted by many contemporary designers. Bulgari, too, is having a very Mughal moment. Three years ago, it developed a smooth new cut, inspired by the aesthetic – the takhti cut has become a focus of the Musa collection. (‘Takhti’ is Hindi for tiles, a reference to those on the roofs of palaces in India, which echo the half-cylinder shape of the cut.)

Lucia Silvestri, creative director of Bulgari jewellery, explains: “It came about after we attended the wedding of our gem supplier’s daughter, and her mother was wearing a traditional necklace of emerald beads that was breathtaking. We bought it from her and our supplier cut them, creating a shape that’s similar to the dome-shaped cabochon, but is actually a halved hexagon... [because of this cut] the stones are bigger, clearer and more intense in colour.”

We see the influences in countless collections and myriad ways, from De Grisogono’s very bold, Italian- Mughal mixing of colours and cuts to subtly refined jewels by Van Cleef & Arpels. There’s a new generation of Indian jewellers (both inside and outside India) harnessing their heritage in contemporary ways – from Amrapali (which uses old-cut and flat-cut stones in bold settings to create jewels on a grand scale) to UK-born Sally Agarwal (who has made the polished but uncut polki diamonds a signature). Nirav Modi uses melon-cut emeralds and rubies to stunning effect and has developed his own, modern version of the Mughal cut to fit the exact design of flower petals, while Mumbai-based Viren Bhagat translates architectural silhouettes, plant and flower motifs and Art Deco lines into 60-70 unique pieces per year. When Cartier unveiled its Étourdissant High Jewellery collection (never was a name more fitting) the influence was unmistakable: Here were the leaf-shaped carved stones, there were the cabochons and everywhere was colour. But, this was no pastiche – the colour scheme was completely fresh, mixing oranges, purples, turquoise and every shade of green.